Information has never been easier to access or harder to trust. In today’s world, corporate marketing and political messaging floods our feed, redefining what it means to learn and to think critically. Every day, we submit our brains to a constant stream of data, notifications, and emotionally charged headlines from news outlets and social media. This environment of overstimulation can make it difficult to extract actual, usable information, leaving us feeling overwhelmed rather than informed. In this era of overstimulation of the primitive brain, it’s easy to shut down or simply react to the loudest signal. Into this landscape enters artificial intelligence, a powerful new tool that promises to reshape how we learn and process the world around us. But using it effectively isn't just about getting faster answers. It's about understanding its unique strengths and, more importantly, its profound limitations. This article explores five ideas about how AI can change our relationship with knowledge—and reveals the uniquely human skills it can never replace.

You Might Be a "Frog Learner" — and AI is Your New Favorite Pond

An old metaphor describes three distinct styles of learning. The Frog hops between topics, driven by a curiosity to discover new connections. The Tortoise moves slowly and deliberately, seeking depth and accuracy in a single subject. The River also explores one domain, but does so over a long period, letting knowledge flow and expand organically. While all styles have their merits, AI seems particularly useful for "frog learners." For those who thrive on connecting seemingly disparate fields, AI flattens the traditional hierarchy of knowledge. You no longer need a specific teacher or "fountain of knowledge" to draw a line between psychology and physics; AI provides immediate access, fueling that connective style of learning. This isn't just a semantic difference; it's a strategic shift. By recognizing AI as an exploratory partner, you can move beyond simple Q&A and fosters understanding to enjoy one’s personal life journey.

To Get Better Answers, Give Your AI a Personality

A common frustration with AI is getting generic or surface-level responses. A powerful technique to overcome this is to assign the AI a specific persona or identity within your prompt. Instead of asking a general question, you frame it through a specific lens, guiding the AI to access and structure its vast knowledge in a more sophisticated way. For example, you could prompt the AI with a scenario and add the instruction: "think of it as if you were Carl Jung...how would he explain this situation." This simple addition forces the model to filter its response through the concepts, vocabulary, and analytical framework of a specific thinker. This transforms your interaction with AI from a simple query to a simulated dialogue with a specific school of thought, unlocking layers of understanding that a generic prompt could never reveal.

AI Has "Book Morality," Not Lived Wisdom

It is critical to understand the difference between an AI's intelligence and genuine human wisdom. An AI's knowledge is built on statistical probability; its core function is to predict the most likely next word based on the immense dataset of books and text it was trained on. It doesn't "understand" in the human sense; it calculates. Consider Abraham Lincoln, a man who, like an AI, learned primarily from books. Yet, when Lincoln read Aesop's Fables, he didn't just process the words; he used them as a springboard for moral reflection and applied them to the crucible of his lived experience. An AI, by contrast, operates with what we might call a "book morality." It's the difference between a "book morality" and an "experiential morality." AI can tell you what is commonly written about a situation, but it hasn't lived through one. Recognizing this distinction is crucial; it helps us use AI for what it’s good at—summarizing collective knowledge—while reminding us to turn to human experience and introspection for genuine wisdom.

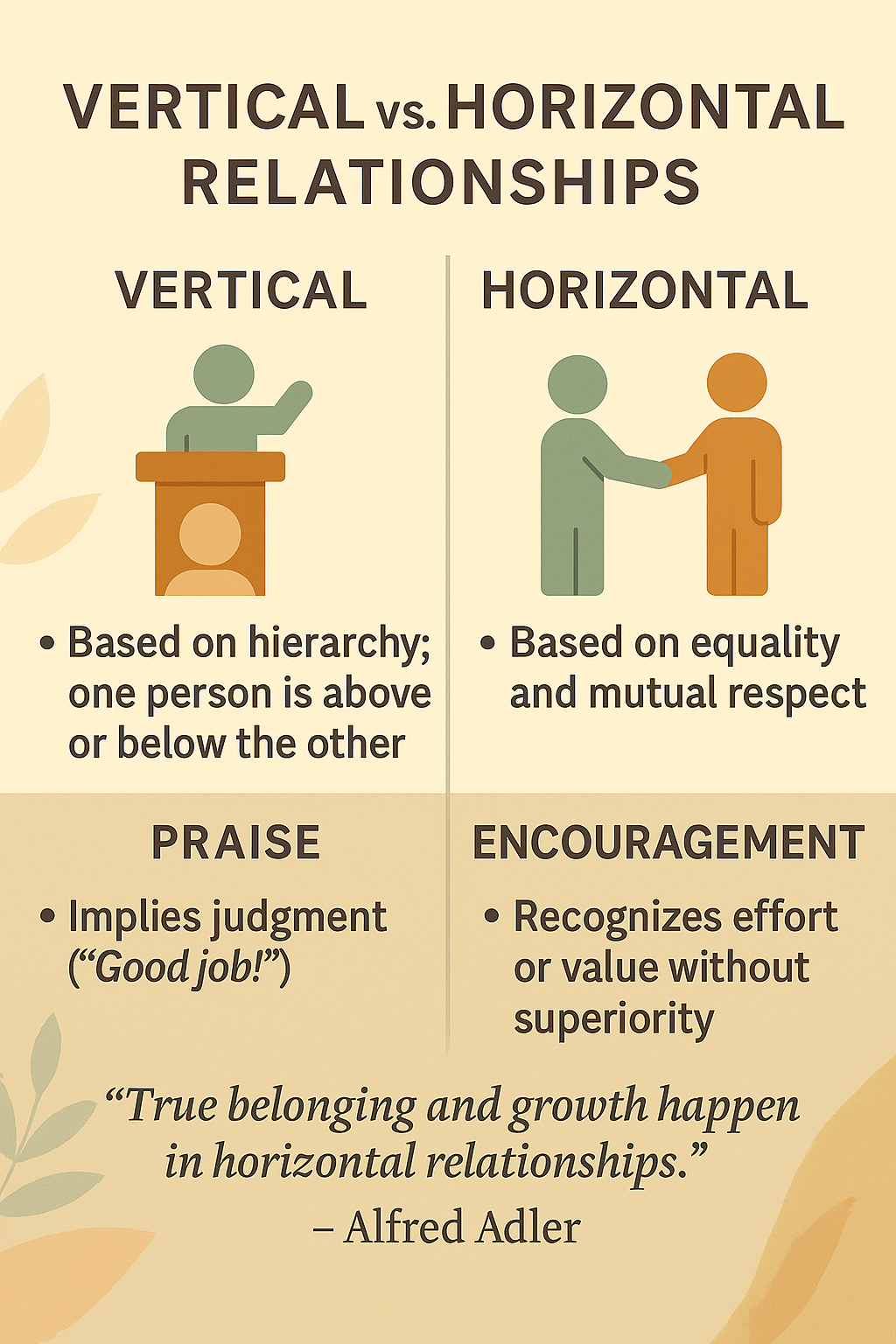

The Most Powerful Learning Tool Isn't AI; It's Other People

While AI can provide endless information, it cannot provide one of the most essential ingredients for deep learning: perspective. This is where Perspective Learning comes in, which is the act of understanding why another person's unique life experiences cause them to connect with information in a way you never could. It's about learning from the emotional and contextual story that shapes their perspective. When we listen to someone else's story, we don't just acquire facts; we gain insight into the emotional weight and personal history that gives those facts meaning. This enriches information with a depth AI cannot replicate. This insight repositions human conversation not as an alternative to AI, but as an essential, irreplaceable complement. While AI provides the data, people provide the meaning. "Oh, I would have never thought of that because I never...went through that situation to give me the skill or the insight to be able to see it that way or have that deeper connection."

Use AI to Find the Signal, Not Just Add to the Noise

In a world of information overload, it seems counter-intuitive that adding another information tool could bring clarity. Yet, when used intentionally, AI can be a powerful filter to reduce noise rather than contribute to it. Instead of endlessly scrolling through sensationalized news feeds, you can use AI to regain control of your information consumption. A practical example is to ask an AI for a non-sensationalized weekly news recap covering specific topics of interest. This allows you to stay informed on key events without the emotional hijacking of constant media consumption. By automating the mundane task of information filtering, we reclaim the cognitive bandwidth our brains need for their highest functions: creativity, imagination, and deep exploration—the very things that define our human intelligence.

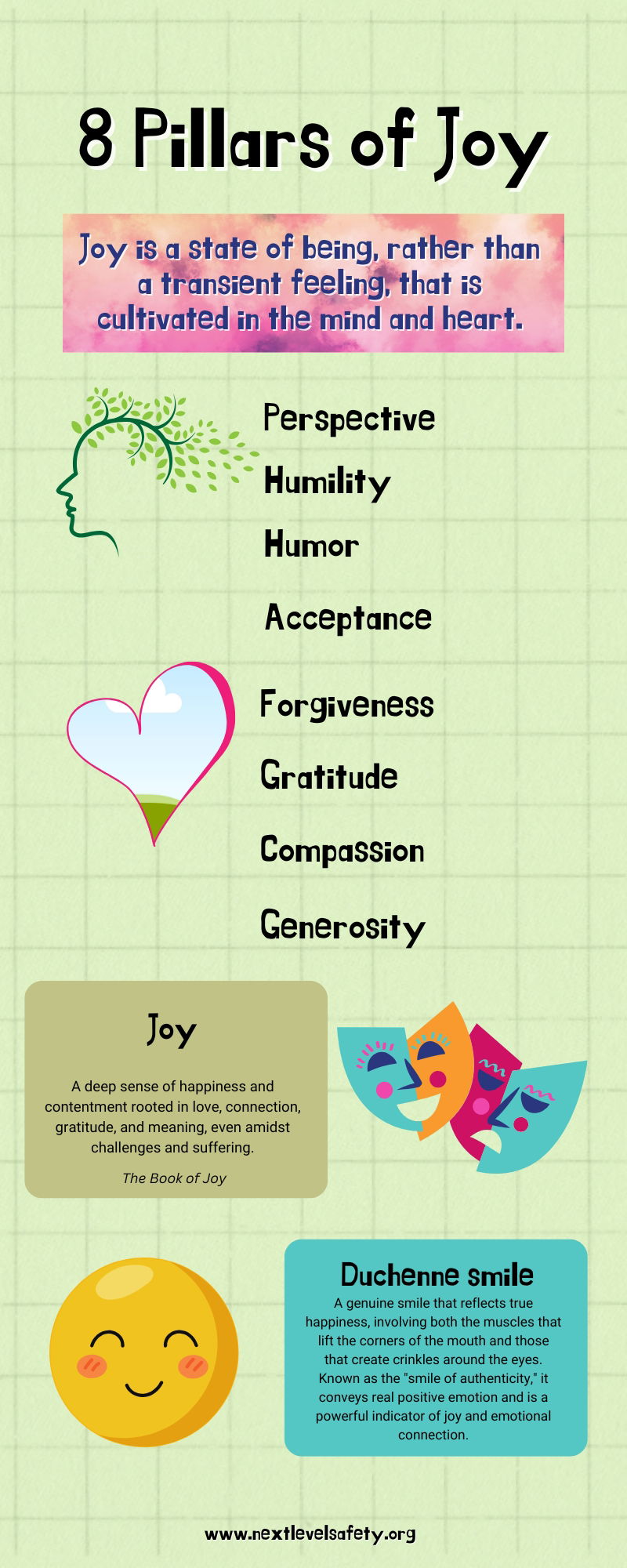

Conclusion: Your Uniquely Human Algorithm

AI is a tool that is flattening knowledge hierarchies and empowering our natural curiosity in ways not since the Gutenberg Press made different perspectives through books accessible. It can serve as a research assistant, a brainstorming partner, and a filter for the noise of the modern world. It allows us to be the "frog learner," making connections we might never have found on our own. However, the path from knowledge to wisdom remains deeply human. True understanding is not built on data alone but is enriched by experience, empathy, and connection with others. AI can process information on the web, but it cannot replicate the insights gained from a single human life. AI can give you the 'what' of global knowledge. But only you can cultivate the 'why' this knowledge matters to you. As you delegate your information gathering, what is one conversation you will have, or one experience you will seek out this week, to invest in your uniquely human algorithm?